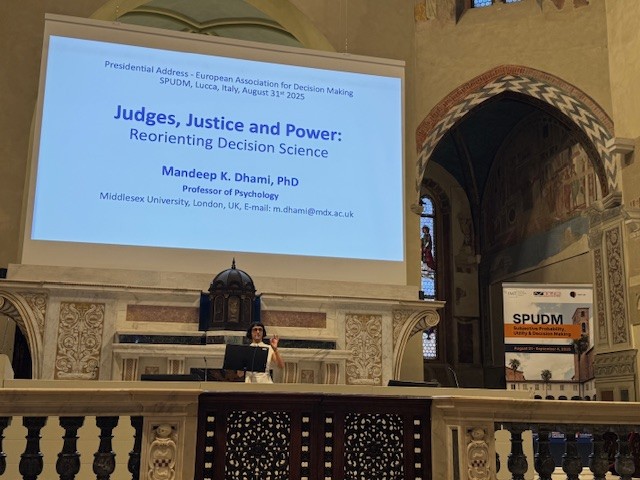

We have an excerpt of Mandeep K. Dhami’s presidential address at this year’s SPUDM meeting in Lucca, Italy.

In this Presidential Address, Prof. Dhami took the opportunity to reflect on the history and contributions of our field, and called for us to reimagine our science. The address will be published in Judgment and Decision Making in due course. For now, here is a summary:

In this Presidential Address, Prof. Dhami took the opportunity to reflect on the history and contributions of our field, and called for us to reimagine our science. The address will be published in Judgment and Decision Making in due course. For now, here is a summary:

Judges, Justice and Power: Reorienting Decision Science

Our field has ambitious goals, and we have had tremendous success both in terms of scientific advances and practical impact. The two dominant schools of thought in our field which view decision competence as either internal coherence or external correspondence, have generated an array of useful methods and a rich set of ideas for studying, understanding and improving human JDM.

But, I ask: can we do even more? And, can do even better? I believe we can.

In focusing on what is a ‘good’ decision, our field has been somewhat narrow, by for example, focusing on ‘accuracy’ relative to a normative benchmark or external criterion, and by valuing instrumental outcomes such as financial gain. However, if we really care about ‘good’ decisions, then I believe we must also care about ‘just’ decisions. In doing so, we demonstrate that we also value justice.

To that end, I would like us to reorient our science to study the exercise of judicial power in the search for justice, and consequently in the service of justice.

Justice is a multifaceted concept, but rarely about profit, material outcomes or even accuracy. For simplicity, justice encompasses fair outcomes (distributive), fair processes (procedural), fair treatment (interactional), fair punishment (retributive), and, also more commonly these days, restoration (repair and reconciliation). In its relational and expressive form, justice remains a product of decisions. As such, justice should be in our purview.

In the justice system, where I have spent much of my career, court judges wield considerable, unfettered power. They interpret and apply the laws passed by legislature, and they can set new legal precedents. Court judges are tasked with upholding the constitution where this is applicable, and they are the ones we rely on to protect our rights and freedoms. Judges punish us if we break the rules, and in doing so, support us if we are wronged. Judges have the power to affect our personal lives, directly, by for example, repossessing our homes, and removing custody of our children.

Beyond the vast reach of judicial decisions, there are other disturbing aspects of judicial power. These include the considerable discretion afforded to judges in decision-making and the lack of personal accountability for the decisions made. Even in jurisdictions or cases where the search for justice sometimes relies on lay people (whom we call jurors), judges wield power by presiding over evidence and testimony presented to jurors, instructing them on how to perform their task, and assessing the quality of jury decisions during appellate review.

The fact that they are called “judges” may lead both them and the rest of us to assume these individuals are good decision-makers and that their decisions are just. Unfortunately, my own research in the JDM field, along with that of others from different disciplines, does not support this assumption. In polite terms, judges can be both irrational and plain wrong.

Nowadays, judicial power is increasingly being shared with, or transferred to, algorithms. And so, we must bring our science to bear not only on human court judges, but on hybrid judge-AI systems, and on the algorithms themselves. Therefore, I call for us to put our intellectual resources into extending and applying our theories and methods in three ways:

(1) Focus on justice as an outcome — alongside, or even above the other sorts of outcomes we routinely study. Let us define with precise theories and models the standard for what makes a decision “just”, as we have already done for what makes a decision “rational” or what “achievement” means in a decision-making context.

(2) Study the exercise of judicial power — decisions made by court judges in both criminal and civil or public and private law, and on a range of matters including criminal, corporate, family, employment and environmental. Let us demonstrate with empirical rigor when and why justice is not served.

(3) Scrutinize the algorithms that are increasingly influencing or replacing judicial power — by, for instance, assessing their computational (reasoning) processes, informational bases and biases, and outcome fairness, as well as studying issues such as judge-algorithm interactions (which include trust in algorithms, algorithm effects of thinking e.g., dual processes, etc), and the legitimacy of ensuing decisions. Let us use the legal domain as an illustration of what our science has to contribute in the age of Artificial Intelligence.

Methodologically, with its array of sophisticated tools, our field is well-equipped to study the exercise of judicial power. However, from a theoretical standpoint, justice does not feature in the foundations of our field, nor in the hugely popular theories and models that have followed. In addition, our field has tended to value instrumental outcomes such as financial gain, rather than relational or expressive outcomes. Therefore, we have some thinking to do if we want to reorient our science to hold powerful judges and their powerful algorithms to account.

Justice can be modelled, measured and improved – but only if we choose to prioritize it. What we need is the will to apply our science where we are not invited but where the stakes are highest. By studying the exercise of judicial power, our field would be working in the service of justice, and be more future proof.

I hope my address will serve as both a reflection and an invitation — a reflection of the achievements of our field, and an invitation to build on them by reimagining our science. Let us judge the judges. Let us judge the algorithms. And let us judge ourselves — by the contribution we make to society.